altMA Alternative MA 2025/2027

Read more

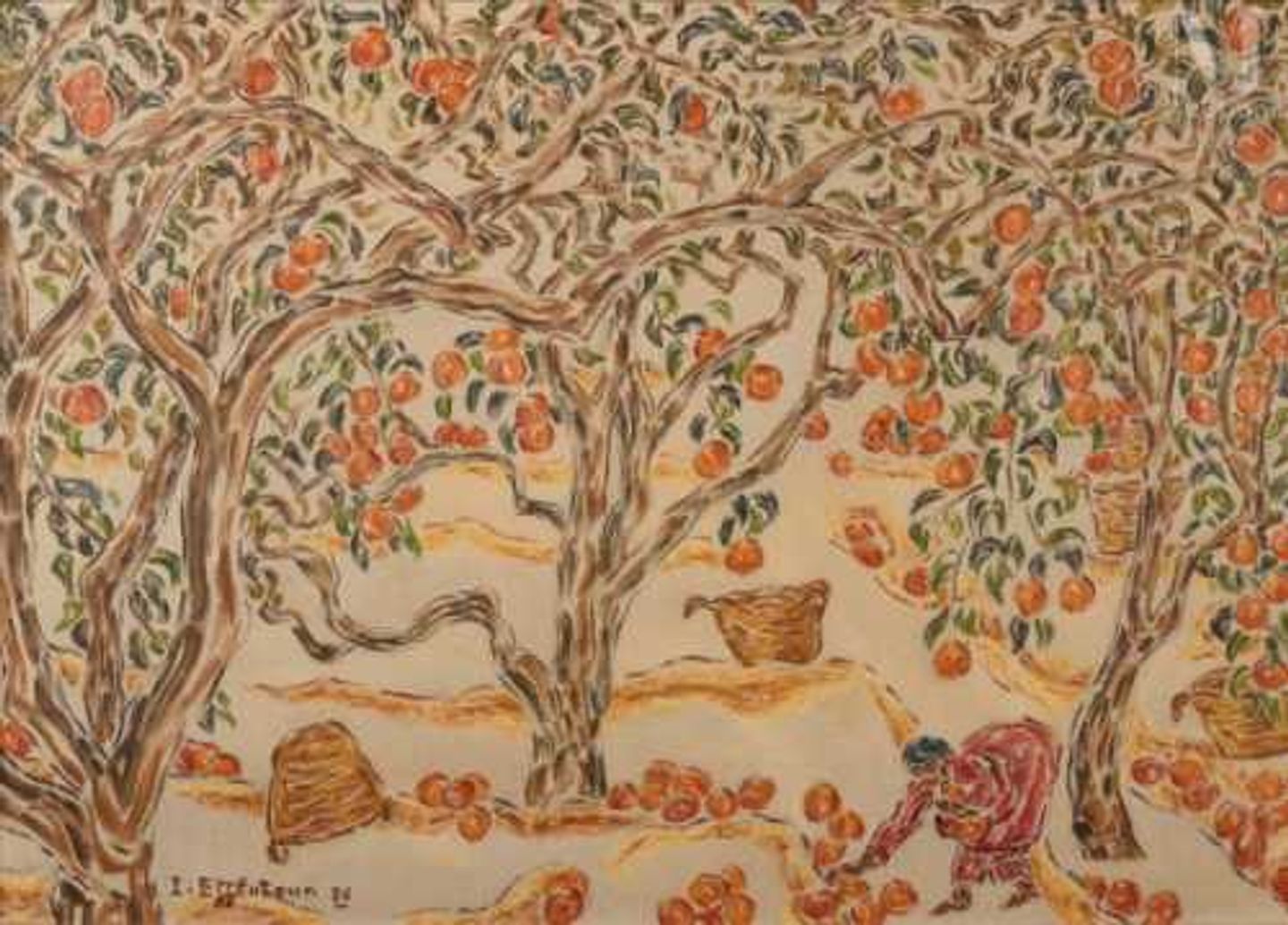

This Alternative MA (altMA) pursues the reconceptualisation of the world through food, reframing a food-scape reality where to develop an artistic practice.

shCO Queer Food 2026

Read more

Food and the queer are intrinsically intertwined, shaping social perceptions, cultural narratives, and personal identities.

shCO Roots: Biopower and Resistance

Read more

Exploring Biopower & Resistance through Food

shCO Queer Food 2025

Read more

Food and the queer are intrinsically intertwined, shaping social perceptions, cultural narratives, and personal identities.